A Beginner’s Guide to Internal Family Systems (IFS)

Healing Your Inner World: With IFS

Welcome! If you’ve ever felt like part of you is anxious while another part is calm, or like you have an “inner critic” alongside a more confident voice, you’re not alone. Internal Family Systems (IFS) is a type of therapy that embraces these different sides of us. It might sound a bit strange at first – after all, how can one person have many parts inside? But think of it this way: just as a family is made up of different members, our mind is made up of different “parts” or sub-personalities, each with its own feelings and roles. And at the center of it all is something called the Self – that’s the calm, compassionate core of who you are.

In this friendly guide, we’ll explore how IFS can help with common mental health challenges like anxiety, depression, trauma, and self-esteem issues. You’ll learn what IFS is, meet the inner “parts” it talks about, and discover how healing happens through understanding and caring for these parts. We’ll keep things conversational and accessible – no therapy degree needed! Along the way, you’ll find practical examples, easy exercises to try on your own, and reassuring real-life applications of IFS. By the end, you should have a clear idea of how IFS works and how it might help you on your mental well-being journey. Let’s dive in!

What Is Internal Family Systems (IFS)?

Imagine your mind as a cozy living room where all your emotions and thoughts are like characters hanging out. Internal Family Systems (IFS) is a therapy model that says we all have these different “parts” of our personality – and that’s completely normal! In IFS, you don’t have one single identity; instead, you have an internal family of parts that might sometimes clash or get along, just like a real family. And just as a family has a guiding parent or wise elder, you have a core Self that can lead with compassion and wisdom.

Developed by Dr. Richard Schwartz in the 1980s, IFS was inspired by the way people naturally talk about “a part of me feels this, another part feels that.” Schwartz realized these inner parts often act like little personalities within us – for example, a part of you might be very critical to protect you from failure, while another part might be playful and childlike. Rather than viewing these inner voices as bad or as a disorder, IFS sees them as members of your inner team who can learn to work together. The goal of IFS therapy is to help you get to know these parts, heal the hurt ones, and restore balance so that your Self is in the driver’s seat of your life.

Key IFS Concepts – Parts and Self: In IFS, there are a few key ideas to understand:

-

Parts: These are the different voices or feelings inside you. Each part has its own perspective and tries to help in its own way. There are three common types of parts IFS often describes:

-

- Managers: These parts run our day-to-day life and try to keep things under control. A Manager part might be the one that makes you work hard, be perfectionistic, or worry about plans. It tries to prevent anything bad from happening. For example, a Manager part might say “Don’t go to that party, you might embarrass yourself,” in order to protect you from rejection or anxiety.

- Firefighters: When strong uncomfortable feelings break through (like sudden panic or sadness), Firefighter parts jump in to douse the flames. They often do this by trying to numb or distract you. A Firefighter might urge you to eat ice cream, play video games for hours, or even misuse substances when you’re really upset – anything to escape the pain quickly. They’re not trying to harm you; they’re just desperate to put out the emotional fire fast, even if their methods are not healthy in the long run.

- Exiles: These are the very hurt parts of you that carry pain, trauma, or deep shame. Exiles often represent younger versions of you that felt hurt or scared, like a “little child” part that still feels the loneliness or fear from long ago. Because their pain is so intense, other parts (Managers and Firefighters) try to keep these Exiles tucked away to avoid overwhelming you. That’s why they’re called Exiles – they’ve been isolated internally. But they truly need care and attention, because they hold the key to healing old wounds.

-

-

Self: At the core of all of us, IFS says there is a Self – the real you, with a capital “S”. Your Self isn’t a part; it’s more like the compassionate leader of your inner family. When you’re in Self, you feel calm, curious, caring, and confident. In fact, IFS describes the Self with qualities often called the “8 C’s,” which include things like Compassion, Curiosity, Calmness, Clarity, Confidence, Courage, Creativity, and Connectedness. That might sound like a lot, but it basically means that when you’re in a good state of mind – patient, kind to yourself, and open-hearted – that’s your Self shining through. The amazing thing is, IFS believes your Self is never damaged, no matter what you’ve been through. It’s like a wise, unbreakable core that can’t be destroyed. Therapy is often about helping your parts trust the Self to lead, so they can relax and let that wise part of you handle things.

How IFS Sees the Mind: Think of a bus where you (Self) are the driver and your parts are the passengers. Sometimes a frightened or angry passenger (say, an anxious part or an angry part) might try to grab the wheel. IFS therapy would help that passenger feel safe enough to go back to their seat, allowing you (your Self) to steer again. All parts are welcome on the bus – none are thrown out – but they travel more peacefully once they trust the driver. In IFS, no part of you is considered “bad.” Even if a part is causing destructive behavior (like a Firefighter leading you to drink too much or a Manager making you overly anxious), IFS approaches it with empathy. We’d say, “Hey, that part is trying its best to help or protect in some way. Let’s understand its role and find a healthier way to meet that need.” This attitude is very different from some approaches that try to fight or get rid of symptoms. IFS is all about understanding and healing from within by helping your parts work together under the gentle leadership of your Self.

According to IFS, it’s normal to have many different parts (sub-personalities) inside us, and a wise core Self. You might picture it like this: the many characters in your thought bubble are all aspects of you, and having them is NORMAL.

Now that we’ve got the basic idea, let’s look at how IFS can actually help with specific mental health challenges. We’ll explore anxiety, depression, trauma, and self-esteem one by one, and show how IFS might approach each of these. Along the way, you’ll see examples of different parts – maybe you’ll even recognize some of your own inner voices – and learn some tips and exercises to start working with them.

Why Try IFS for Mental Health?

You might be wondering, “IFS sounds interesting, but how can understanding my inner parts actually help me feel better?” Great question! The strength of IFS is in its compassionate, non-judgmental approach to whatever is going on inside you. Many of us tend to fight ourselves: we hate our anxiety, beat ourselves up for being depressed or insecure, or feel ashamed of our trauma responses. IFS offers a different path: self-compassion and insight instead of self-criticism.

Here are a few reasons why people find IFS helpful for mental well-being:

- It normalizes your experience: When you realize that it’s normal to have conflicting feelings (because you have different parts with different needs), you feel less crazy or overwhelmed. For example, one part of you wants to stay in bed, another part urges you to get up and exercise – rather than feeling like “What’s wrong with me?”, IFS would say it makes sense: an exhausted part needs rest and a proactive part wants you to be healthy. Both have good intentions.

- Every part has a positive intent: Even if a behavior is harmful (like excessive drinking, self-harm, or lashing out in anger), IFS suggests that the part driving it is trying to help or protect you in some way. This doesn’t excuse bad behavior, but it changes how we address it. Instead of attacking that behavior with shame, we get curious: why is that part so desperate? What pain is it trying to soothe? This approach can reduce internal conflict and help you change habits more gently.

- Healing at the root: IFS works by healing the wounded Exiles that are often at the root of anxiety, depression, and low self-esteem. By caring for those hurt inner parts (maybe a younger you who felt rejected or unsafe), your system can let go of extreme protective strategies that cause distress. In IFS terms, we call this unburdening – the hurt part releases the painful beliefs or emotions it’s been carrying (like “I’m not good enough” or trauma memories) and transforms into a lighter, more positive role. When that happens, all the parts that were working to protect that wound can relax because there’s no big emergency inside anymore. That’s when lasting change happens.

- You are in charge of the process: A lovely thing about IFS is that you (your Self) are seen as the main healer. The therapist is more like a guide helping you access your Self and communicate with your parts. Many people find this empowering – it’s not someone else fixing you, it’s you learning to lovingly understand yourself. This can build confidence and self-esteem in itself. Even if you’re new to therapy, IFS can feel very collaborative and respectful of your own pace and intuition.

- Works with many issues: IFS isn’t just for one type of problem. It’s been used to help people with anxiety, depression, trauma (including PTSD), relationship issues, addiction, eating disorders, and more. It’s a flexible model that adapts to you. For instance, if you have anxiety, you might have an overactive protector part; if you have depression, perhaps some parts have given up hope to protect you from disappointment. IFS can address both by honoring what those parts are trying to do and helping them find a new role.

Now, let’s get specific and see how IFS can assist with the four big pain points mentioned: anxiety, depression, trauma, and self-esteem. As we go through each, remember that IFS is about listening to your inner parts with curiosity and care. You might start to identify what some of your own parts are after reading these sections. That awareness alone is a great first step!

IFS and Anxiety: Calming Your Worried Parts

Anxiety can feel overwhelming and all-consuming, like a constant alarm ringing in your mind. Have you ever experienced thoughts racing (“What if this goes wrong? What if that goes wrong?”), a tightening in your chest, or maybe an urge to avoid certain situations? In IFS terms, these experiences aren’t you being “too sensitive” or “irrational” – they’re anxious parts of you trying very hard to keep you safe.

How Anxiety Shows Up as Parts: Often, anxiety is the voice of one or more protective Manager parts. For example:

- The Worrier – a part that’s always scanning for danger and thinking of worst-case scenarios. It might bombard you with “what if” questions: What if I mess up? What if something bad happens? This Worrier believes that by keeping you on high alert, it can prevent disaster.

- The Critic – a harsh inner voice that scolds you (“Why did you say that? That was stupid!”). Surprisingly, this part often criticizes you not to make you feel bad, but to push you to do better or to prevent others from criticizing you first. It’s as if it’s saying, “If I’m tough on you, maybe you’ll stay in line and nobody else will hurt you.”

- The Perfectionist Manager – a part that insists everything must be in perfect order and under control. It might make you double- and triple-check things, or avoid trying new things because they’re too uncertain. Its goal is to avoid any chaos or failure that could lead to emotional pain.

You may also notice physical feelings – a racing heart, tight muscles, butterflies in the stomach. IFS sees those as ways a part might be communicating. A tight chest or knot in the stomach might be an anxious part saying, “I’m scared.” A headache might be a part trying to shut things down because it’s all too much. Our parts often speak through the body.

IFS’s Compassionate Take on Anxiety: Rather than saying “Ugh, go away anxiety, I hate you,” IFS encourages us to approach these anxious parts gently. Remember, each part has a good intention. That Worrier is exhausting, yes, but it loves you and wants to protect you from failure or harm. That inner Critic is harsh, but it thinks being tough on you will motivate you or shield you from others’ judgments. In IFS therapy, a clinician might help you separate (unblend) a bit from the anxiety – so instead of “I am anxious,” you might say “A part of me is feeling anxious.” This slight shift in language already gives you more breathing room. You’re acknowledging it’s just a part of you, not the whole you, and that implies you (Self) can interact with it.

Calming and Caring for Anxious Parts: Once you identify an anxious part, the next steps in IFS are usually to get to know it. You can do this on your own, too, with some mindfulness:

- Step 1: Notice and Name. When you feel anxiety, pause and notice where you feel it in your body or what thoughts are present. Then try naming it: “I notice there’s a worried part here” or “I have a part that’s really anxious about this meeting.” It might feel odd, but many people find this immediately reduces the intensity of the feeling. It’s the difference between being in a storm versus observing it from a slight distance.

- Step 2: Send Comfort from Your Self. Take a few slow breaths and see if you can tap into a more compassionate stance – maybe imagine how you’d reassure a nervous friend or a scared child. From that calmer place (your Self), gently acknowledge the anxious part. You might internally say, “I see you’re really worried. I’m here with you.” This isn’t to make it vanish instantly, but to show the part that it’s not alone and that you, the Self, are listening.

- Step 3: Get Curious (Ask Why). If it feels right, you can even ask the anxious feeling, “What are you afraid of right now?” or “What do you need me to know?” Then just listen. Perhaps a thought pops up like “I’m afraid we’ll fail” or an image arises of a past time you felt embarrassed. You might discover the worry is linked to an old memory (like a younger part of you, an Exile, that felt ashamed in school, which is now triggering the anxiety before a presentation). Understanding where it’s coming from helps you address the real concern. For example, if the worry is “I don’t want to be laughed at,” you can respond, “I understand. I (Self) will do my best to handle things. I won’t let anyone harm us. I appreciate you trying to help.”

Example – Facing a Social Situation: Let’s say Jason feels intense anxiety about attending a social event. His heart races and his mind says “Stay home, you’ll just make a fool of yourself.” Using IFS, Jason recognizes this as a Manager part trying to protect him from potential rejection. He takes a deep breath and silently dialogues with it: “I get that you’re worried I’ll be judged. It makes total sense you want to keep me home where it’s safe. Thank you for looking out for me. How about we compromise – I’ll go for just 30 minutes and if it’s awful, I promise I’ll leave. Could you ease up just a bit and let me try?” By acknowledging the part’s fear and appreciating its intent, Jason finds his anxiety dial turns down slightly. The part feels heard. It’s still cautious, but it’s not fighting him as hard, because it trusts Jason a little more. Jason goes to the event, and any time the anxiety flares (e.g., walking into the room), he reminds that part, “It’s okay, I’ve got this.” This is a real example of how someone might practically apply IFS self-talk to manage anxiety in the moment.

Techniques to Soothe Anxiety with IFS:

- Mindful Breathing with Your Parts: One simple exercise is to sit quietly and breathe deeply. As you exhale, imagine sending comfort or warmth to the anxious part of you. Sometimes IFS practitioners suggest visualizing a safe place in your mind – perhaps a cozy cabin or a peaceful beach – and inviting your anxious part to relax there for a while, reassuring it that you will handle the outside world for now. This kind of visualization gives anxious parts “permission” to let go for a bit.

- Journaling Dialogue: Write a back-and-forth conversation in a journal. You write a question or statement as your Self (e.g., “What are you worried about?”), then let the anxious part respond in writing (“I’m scared people will judge us.”). Continue the dialogue, writing both sides. This might sound quirky, but it’s a powerful way to uncover what’s beneath anxiety and to provide comfort. Seeing it on paper also helps you stay in Self while witnessing the part’s concerns.

When Anxiety Runs High: If you have very intense anxiety or panic attacks, you may have multiple parts all activated (a panicky Firefighter making you want to flee, a Manager barking at you to “calm down right now!”, etc.). In such cases, it can help to ground yourself first – using your senses (look around and name things you see, feel your feet on the floor) – basically, calm your body. Then, later when you’re in a safer-feeling moment, you can reflect on what parts were active. In therapy, an IFS therapist would help create a safe atmosphere and guide you to gently explore these dynamics, often finding that a very scared Exile underneath needs care. But even on your own, you can start by acknowledging “Wow, a lot of me was terrified; those parts really took over.” No judgment – just noticing and perhaps thanking them for trying to protect you, even though it was overwhelming.

Remember, the goal is not to eliminate anxiety (we actually need a little anxiety to keep us safe sometimes), but to change your relationship with it. Instead of anxiety being a monster that controls you, it becomes something more like a concerned ally who just needs some guidance and reassurance. With practice, your anxious parts learn to trust your Self more, and anxiety loses some of its grip on your life.

IFS and Depression: Befriending the Blues

Depression often feels like a heavy, dragging weight or a numb emptiness. You might hear thoughts like “What’s the point? I’m just not good enough. Nothing will ever change,” and feel an urge to isolate or give up on things you used to enjoy. How might IFS make sense of these painful experiences? Just as with anxiety, IFS sees depression not as one monolithic thing, but as the state of your inner system when certain parts are dominant and your Self feels far away. Let’s break that down.

Understanding Depressed Parts: People with depression commonly have parts that contribute to that shut-down, hopeless feeling. Some examples:

- The Inner Critic (Manager) – shows up here too, as in anxiety, but in depression it might be relentless in telling you negative beliefs about yourself: “You’re a failure. You’ll never be happy. Why bother trying?” This part might think it’s protecting you by lowering your expectations (so you won’t be disappointed) or by punishing you (thinking maybe it can force you to improve by being harsh). Unfortunately, it often backfires and just makes you feel worse.

- The Despairing Part – this could be an Exile that carries deep pain or sadness. Maybe it’s holding old wounds of loss, rejection, or worthlessness. When it overwhelms you, you feel that heavy despair and might have thoughts of hopelessness or even suicidal ideation. Other parts then might step in to numb this despair (like sleeping a lot – a common Firefighter strategy in depression).

- The Numb Protector – a Firefighter type of part that might respond to pain by numbing your feelings entirely. You might feel emotionally flat or disconnected from life. This part’s motto is “Shut down to survive.” It’s like emotional circuit-breaker, flipping off the switch so you don’t feel the hurt – but consequently, you don’t feel much joy or interest either.

People often describe feeling “disconnected from myself” or “like a shell” when depression is strong. In IFS terms, it’s as if your parts have pushed the Self so far back (in an attempt to shield it from pain) that you hardly feel that core you anymore. The protective parts are running the whole show by either numbing, criticizing, or wallowing in despair, because they think that’s the only way to cope with the burdens being carried inside.

IFS’s Approach to Depression: One of the first steps in IFS is often to build a relationship with that critical part in a different way. Instead of accepting its insults as truth, or fighting it head on (which is like arguing with yourself and can leave you more exhausted), you approach it curiously: Why are you so critical? What are you afraid would happen if you didn’t do this? Many people find that when they actually ask and listen, they get answers like “If I don’t criticize you, you’ll get your hopes up and then be hurt” or “I’m afraid if you don’t feel bad, you’ll do something risky.” It sounds strange, but even these cruel-seeming parts are trying to help by hurting you first before anyone else can, or by keeping you in a low mood so you don’t have the energy to take risks that might lead to pain.

By understanding this twisted kind of caring, you can start to feel some compassion for the part of you that’s depressive or critical. After all, it’s bearing a hard job – imagine a part of you believes it’s responsible for protecting your very soul by keeping you in a dark room. That’s a heavy burden for it, too.

Working with Depression in IFS:

- Acknowledge the Darkness: Sometimes just admitting “A part of me is feeling very hopeless right now” is a relief. Instead of I am hopeless (100% fused with it), you recognize it as a part. You might even visualize that part – perhaps you see an image of an exhausted figure slumped on the ground, or a small child who looks defeated. Use whatever image or sense comes to mind. You can then mentally approach it (Self to part) and say, “I’m here. I see you’re carrying so much sadness.” Not trying to fix it immediately, just being present. That alone is something new – often our reaction is to ignore or squash depressive feelings. Here you’re doing the opposite: bearing witness kindly.

- Find Out the Protective Intent: As mentioned, ask gentle questions to the depressed-feeling part or the inner critic voice that comes with it. Like, “What are you afraid would happen if you didn’t make me feel this way?” or “How are you trying to help me by making me so down?” The answers might come as a thought, a feeling, or even just a sense, like “It’s safer not to care” or “If we isolate, we can’t get hurt by people.” These responses give clues. For example, if the answer is about not getting hurt by people, then we know there’s likely an Exile part inside that has been hurt badly before (perhaps by bullying, betrayal, etc.), and so the system is using depression as a way to protect against further harm (by withdrawing from relationships).

- Appreciate the Effort, Then Negotiate: It might feel weird, but try thanking that part for trying to help. “Thank you for protecting me. I get that you’re trying to shut down the pain.” This doesn’t mean you like being depressed, of course not. It just means you see the reason it’s there. Often these parts never got recognition; they only get our scorn. Appreciation can soften them a bit. Once the part feels understood, it may be willing to let you (Self) step in with new ideas. For instance, you can negotiate: “Would you be willing to let me try something to help our pain, instead of you keeping us shut down all the time? Maybe we can talk to someone, or write about what hurts, or go for a short walk – just to see if it might help. If it feels too dangerous, I promise I’ll check back in with you.” This way the part doesn’t feel like you’re just going to yank away its role without a replacement. You’re collaborating.

Example – Easing a Depressive Part: Sasha wakes up and immediately feels that heavy cloud: “It’s pointless to get up. Nothing good will happen today.” Instead of forcefully pushing herself (or just succumbing to staying in bed all day), she tries an IFS approach. She closes her eyes and notices a part of her really doesn’t want to face the day – she pictures it as a tired, grey cloud-like figure. Sasha mentally sits beside it and says, “I see you want to shut everything out. You’re so tired and done with it all. I’m here now.” She gets an emotional response – a wave of sadness. She senses this part has been holding a belief like “Why try? We’ll just fail.” Sasha recalls how in her childhood, whenever she got excited about something, a parent would criticize or punish her, so she learned not to show enthusiasm. Ah – this depressed part formed to protect her from being hurt by disappointment. She gently acknowledges this: “I know you learned it’s safer to not hope for anything. That really helped us get through those tough years.” In showing understanding, she feels a slight shift – the heaviness lessens a little, almost as if that part sighs, “Finally, you get it.” She then continues, “Maybe today, I can handle a bit more. How about I take a shower and see how we feel? If it’s too much, I’ll let you rest more. But I’d like to try because some other part of me wants to see the sun.” The part doesn’t object (if it did, she’d negotiate more), so she slowly gets up and showers. This small act of Self leadership, done in cooperation with her depressed part, helps Sasha feel a tiny spark of energy. It’s not a miraculous cure-all, but it’s progress – she’s not fighting herself as much, but working with herself.

Reigniting Self-Esteem: Depression and self-esteem are closely tied, so working with those critical and despairing parts gradually improves how Sasha (and you) feel about yourself. As the hurt Exiles share their pain and get compassion (from you or with a therapist’s help), they begin to release those burdens of “I’m worthless” or “It’s hopeless.” They might transform – for example, a sad inner child exile might, after feeling heard and loved, turn into a more hopeful, playful part of you that brings back some spark. When that happens, the protective parts don’t have to be so heavy-handed. The Critic can step back or maybe even take on a new role (sometimes critic parts become encouragers once they trust you – imagine that, an inner coach that actually supports you instead of cutting you down!). The numbness can thaw because it trusts that you won’t be overwhelmed now – you’re handling the pain.

It’s important to note: if you have severe depression or suicidal thoughts, seeking a professional is crucial. IFS can be done both in therapy and as self-help, but with very deep depression, having the support of a therapist to guide the process can be life-saving. They can ensure your parts don’t overwhelm you and that you move at a safe pace. That being said, even with professional help, you are still the one doing the inner healing work in IFS, and many find that empowering.

IFS and Trauma: Healing the Wounded Parts

Traumatic experiences – whether big events like abuse or accidents, or smaller chronic hurts like ongoing childhood neglect – leave a deep mark on our inner system. In IFS, trauma is understood as those experiences that create Exiles carrying extreme fear, pain, or shame, and a whole bunch of protective parts that form to prevent you from ever feeling that pain again. If you’ve been through trauma, you might have triggers that set off intense reactions seemingly out of nowhere, or you might feel numb and disconnected. You might have flashbacks, nightmares, or strong emotional surges that feel out of control. All of these are signs that some inner parts are still in trauma-time – stuck in the past, reliving the hurt – and other parts are frantically trying to manage or extinguish those feelings.

How Trauma Lives in Parts: Let’s illustrate with an example. Alex experienced a car accident in the past. In the moments of the accident, a young terrified part of him (an Exile) got stuck in panic and helplessness. After that, anytime Alex even approaches a car, that Exile’s terror threatens to surge up (“We’re going to die!”). To protect Alex from being flooded by that terror, a Manager part steps in as hyper-vigilance (scanning the road obsessively, mapping every route, avoiding driving altogether whenever possible). If he has to drive, maybe a Firefighter part comes in to numb him – he dissociates (feels unreal or checked-out) while driving so he doesn’t feel the fear. These strategies might keep him functional, but the underlying terror remains unhealed.

That’s a more acute trauma example. In complex trauma (like prolonged childhood abuse), you might have many Exiles of different ages, carrying beliefs like “I’m unsafe,” “I’m unlovable,” or “It was my fault,” and a host of protectors – some may be aggressive (anger that flares up to push people away when you feel even a hint of threat), some may be avoidant (parts that make you socially anxious or isolate you), some may use numbing strategies like substance use, self-harm, or spacing out.

IFS as a Trauma-Informed Therapy: IFS is considered very trauma-informed because it respects the protective function of all these responses. It doesn’t force you to dive into traumatic memories or overwhelm you with emotions. In fact, a fundamental principle in IFS is you only go as fast as the slowest part will allow. This means if a protector part is blocking you from remembering or feeling something, the therapist will not bulldoze past it. Instead, they (and you) will talk to the protector and get its permission gradually by building trust. This ensures that when you do finally work with a traumatic memory (the Exile carrying it), all the protectors are on board and are helping rather than fighting the process. That makes the healing experience much safer and often more thorough, because you’re not re-traumatizing yourself; you’re healing in a coordinated way.

Healing Trauma Through IFS:

- Establish Safety First: Before touching the trauma, IFS therapy often involves a period of just getting to know and comforting the protective parts. You might spend several sessions simply appreciating how your anger has protected you, or how your numbness has kept you stable. This might feel like “Am I even doing therapy?” but it’s crucial. By doing so, you (and the therapist) are basically earning the trust of your inner guardians. You might even make agreements like, “Okay, I have a very sad, young part that cried during that memory, but I promise I won’t go to that place until you (protector) think we’re ready. Let’s work together.” This kind of inner contract helps those guards relax a tiny bit.

- Witnessing the Exile’s Story: When protectors agree, then you can turn toward the Exile (the traumatized part). With the calm presence of Self (and the therapist holding a safe space), you gently invite the Exile to share what it’s holding. This could be recalling what happened, or simply letting that part express feelings it couldn’t express then. Sometimes it’s wordless – you might just shake or cry as the part releases terror or grief. Importantly, you (Self) stay present with it, offering comfort, like “I’m here with you now. You’re not alone in that anymore.” In IFS, they call this witnessing – the part shows you what it’s been carrying, and you witness it with compassion.

- Retrieving and Unburdening: These are IFS terms for the healing moment. Retrieval might mean you imaginatively “go back” to that time and, as your mature Self, remove the child part from the harmful situation. For example, you might visualize entering the memory, scooping up that hurt child, and bringing them to a safe place (like your present-day home, or a fantasy safe spot). This is powerful for trauma – it gives the inner child the rescue they never got. Then comes unburdening – this is where the Exile releases the burden it’s carried. Burdens are the painful beliefs or emotions from the trauma (“It was my fault,” “I’m dirty,” “I’m in danger”). An unburdening visualization might be imagining the child taking a heavy backpack off, or removing black tar from their heart, or crying out all the tears – whatever feels right – and then taking in something good (light, love, etc.). People often feel a huge relief at this stage – many describe feeling lighter, or that something has shifted internally. The part is no longer stuck in that time; it now exists in the present, where you (Self) can care for it.

- Reorganizing the System: After an unburdening, your protectors often change. If that terror is gone or greatly reduced, the hyper-vigilant part might take on a new role, like helping you be thoughtfully cautious but not paranoid. The angry protector might realize it doesn’t have to explode at minor triggers because the underlying wound is healed – it might relax or channel its energy into something positive, like assertiveness or passion for a cause. Essentially, the whole internal family reorganizes into a healthier state. It’s like a true healing of an internal injury – the “infection” of trauma is cleared, so the “symptoms” can subside.

Real-Life Example of IFS Trauma Healing: Maria has a trauma history of childhood emotional neglect. She always felt unseen and unwanted. In her adult life, this manifests as a deep-seated loneliness (an Exile that feels like a sad little girl) and a protective part that makes her very clingy in relationships – she panics at any sign of someone pulling away, bombarding them with texts or getting extremely anxious (this is a Firefighter trying to pull people close to avoid feeling that old abandonment). Another protector is her numb part that sometimes just shuts her emotions off when she’s overwhelmed – she goes robotic for days. In IFS therapy, Maria first spends time getting to know the clingy part and the numb part. She learns the clingy part truly fears being abandoned and left to feel that old loneliness, and the numb part steps in when the clingy one fails, numbing her to survive the heartbreak. With the therapist’s help, Maria genuinely thanks these parts: “Thank you for trying so hard to help me feel loved and to protect me from pain.” They warm up to her, and eventually allow her to approach the lonely child Exile. In a deep session, Maria envisions meeting that little girl who is hiding under a bed crying. As her Self, Maria gently talks to her: “I’m so sorry you felt so alone. I see you. I want you. You are precious to me.” She imagines holding the child, letting her sob in her arms. (Maria herself is crying at this point in reality – it’s a release of years of grief.) She then invites the child to leave that dark house of her childhood and come live with Maria in the present. The child part “unburdens” by handing Maria a grey ball of sadness from her chest, and Maria tosses it away in the visualization. They fill that space with a warm golden light of love. After this session, Maria feels different. In the following weeks, she notices she doesn’t panic as much when her friend doesn’t text back immediately. The clingy protector still gets triggered occasionally, but Maria can calm it by saying “Hey, I’m here, you’re not alone anymore, remember? We have that little girl with us and she’s feeling loved now.” The urgency drops. Her numb part also steps in less frequently, because there’s less overwhelming pain to avoid. Maria reports gradually feeling more secure and present in her relationships, as that trauma wound of neglect is healing.

Important Note: While IFS can sound almost magical in how it heals trauma, it’s a process and often works best with a skilled therapist when dealing with significant trauma. Trying to do deep unburdenings on your own can be hard – you might get stuck or overwhelmed if protectors aren’t fully on board. So, use self-IFS for understanding and day-to-day soothing, but consider seeking an IFS-trained therapist for the heavy stuff. The good news is that IFS therapy provides a map and a sense of hope: it tells you that no matter how hurting your inner parts are, they can be healed. People often feel a lot of hope when they learn about IFS because it means those traumatic memories don’t have to haunt you forever; there’s a pathway to truly transform them.

IFS and Self-Esteem: Growing Self-Compassion and Confidence

Do you have an inner voice that frequently tells you that you’re not good enough, or compares you to others and says you come up short? Many of us do – it’s often called the inner critic (which we met earlier as a Manager part). Self-esteem issues essentially come down to parts of us carrying negative beliefs about ourselves, often born from past experiences where we felt inadequate or unworthy. The result is that even when evidence shows we’re capable or loved, those parts make it hard to truly feel it.

How Parts Influence Self-Esteem:

- We’ve already talked about the Inner Critic – that part can seriously drag down self-esteem by constantly pointing out flaws or mistakes. Perhaps you have a critic part that says things like, “You’re so stupid,” “You’ll never succeed,” or “No one really likes you.” It might use the voice of a critical parent or bully from your past – essentially echoing those old messages.

- There may be an Exile part carrying shame – a deep sense that “I am bad” or “I’m not worth loving.” Shame is one of the hardest feelings, and many behaviors (perfectionism, people-pleasing, even arrogance) are actually shields against feeling that core shame. If you struggle with self-esteem, chances are you have an exile who at some point in life believed something was wrong with them (kids often internalize blame, thinking “it must be me”), and that part needs serious compassion.

- Sometimes, a person with low self-esteem also has a People-Pleasing Manager part – a part that goes above and beyond to make others like you, because your worth is tied up in external validation. This part might make it hard for you to say no, set boundaries, or express your true needs for fear of displeasing others. While it might earn some approval, it often leaves you feeling unheard and resentful, ironically reinforcing that idea that your own needs or identity aren’t important.

Building Self-Compassion (the Antidote to Low Self-Esteem): One of IFS’s gifts is that it directly fosters self-compassion. As you practice relating to your parts kindly – even the ones that frustrate you – you are literally exercising the muscle of self-love. Over time, this changes how you feel about yourself fundamentally. Here’s how IFS can help improve self-esteem:

- Transforming the Inner Critic: Using IFS, you approach your critic part like a concerned friend rather than an enemy. You might say, “I know you’re trying to help me avoid failure by pointing out all my faults, but it’s really hurting me. Could you try a different approach?” As crazy as it sounds, inner critics can soften and take on supportive roles. What if that voice that says “You’re an idiot” could eventually say “Hey, I know you can do this. I believe in you”? It’s possible – people have reported their inner critic becoming an inner coach once the pain driving it is addressed. In practical terms, next time you catch yourself in self-critical thoughts, pause and identify that as a part. Respond to it with something like, “I hear you’re worried about me messing up. Let’s talk later, but for now, I’ve got this.” By not letting it run wild and also not squashing it with hatred, you strike a balance that preserves your confidence.

- Healing Shameful Exiles: Low self-esteem often traces back to experiences of feeling judged, bullied, or not enough. Through IFS, you find those younger parts in you that felt that way and give them the love and reassurance they missed. For instance, if 8-year-old you felt stupid because a teacher humiliated you, there’s a part of you still holding that belief “I’m dumb.” IFS work would have you (or you with a therapist) revisit that scene in imagination, stand up for that child (“You’re not dumb at all, the teacher was wrong to say that!”), and maybe remove them from that situation and give them something they needed – a hug, encouraging words, etc. When that part lets go of the belief “I’m dumb” (unburdens it), your overall self-esteem rises because deep down you no longer believe that lie. Instead, that once-shamed part might now carry a feeling of pride or competence, contributing positively to your self-concept.

- Empowering Self (You) as Leader: Self-esteem grows as you experience your Self taking charge in your life. The more you see yourself handling inner conflicts with compassion, the more confidence you build that “Hey, I can deal with my emotions. I can understand myself.” This naturally extends outward too: if you can lead internally, you start to lead externally – making choices that reflect self-worth (like setting healthier boundaries, pursuing goals you care about, treating yourself with kindness).

Example – From Self-Criticism to Self-Encouragement: Elena struggles with low self-esteem, especially at work. Whenever she makes even a tiny mistake, a voice in her head screams that she’s a failure and everyone will find out she’s incompetent. She’s tired of feeling so terrible about herself, so she tries an IFS-informed exercise. She imagines that critical voice as a character – she sees a stern, frowning figure with a clipboard. Elena (Self) says to it, “I know you’re trying to help me do well by scaring me. But it’s crushing my confidence. What are you afraid of if you don’t do this?” The part replies in her mind, “If I don’t point out your errors, you’ll get lazy and then you’ll really mess up big and be fired.” Elena has a bit of an aha moment: this part actually thinks it’s being useful, like a tough coach. She replies, “I appreciate you want me to succeed, but the way you’re going about it is hurting us. I need encouragement, not just criticism. Can you try reminding me of what I’m good at too?” The part is skeptical but agrees to ease off a bit. Over the next week, whenever Elena hears that insult, she pauses and says something kind to herself deliberately: “It’s okay, nobody’s perfect. I can learn from this.” She essentially speaks from Self, modeling the job she wants her inner coach to do. Bit by bit, that critic’s voice starts including a new line: “Don’t screw up – but actually you did well on X yesterday, so maybe you’ve got this.” It’s almost weird for Elena to hear, but she’ll take the positivity! She finds her overall esteem improving; she feels less defined by momentary mistakes and more aware of her strengths. This is ongoing work, but it’s trending upward.

Self-esteem Quick Tips with IFS Flair:

- Make a List of Your Parts that affect your self-esteem. Perhaps: The Critic, The Comparer (who always compares you to others), The People-Pleaser, etc. Jot down what each one says or does, and what it’s trying to achieve for you. This externalizes them so they feel less like “this is just how I am” and more like “this is a part of me that I can work with.” You might notice, for example, that your Comparer (that scrolls Instagram and makes you feel inferior) is actually longing for acceptance. With that knowledge, you can catch it and say, “Comparing isn’t truly helping us feel accepted. How about we reach out to a friend instead, or do something we enjoy?” It takes practice, but you’re retraining those parts.

- Affirmations from Self to Parts: Instead of generic affirmations (“I am worthy” which some parts might roll their eyes at), try affirmations directed at your parts: “All parts of me are welcome.” “I know everyone inside is trying their best.” “I can learn to love all these parts of me.” These statements set a tone of acceptance in your inner world. When parts feel accepted, they relax, and your overall sense of well-being improves.

Self-esteem built on inner acceptance tends to be more resilient than self-esteem built on external validation. IFS helps you cultivate that inner acceptance by fundamentally reshaping the relationship you have with yourself (selves). You become more of an inner best friend than an inner enemy to yourself. And as corny as “befriending yourself” might sound, it truly is the foundation for feeling comfortable in your own skin.

The three primary types of parts in IFS – Managers, Exiles, and Firefighters – each play a role in how we cope with life’s challenges. By understanding their roles (as shown above) and working with them, we can transform anxiety, depression, and trauma responses into a more balanced state. In doing so, we naturally build self-esteem based on self-understanding rather than self-judgment.

Getting Started with IFS: Practical Exercises for Beginners

By now you’ve got a good idea of what IFS is and how it views common issues like anxiety or low self-worth. But it might still feel a bit abstract. Let’s bring it down-to-earth with some simple exercises you can try on your own. Remember, these are beginner-friendly. You don’t have to get it perfect – just approach this with a spirit of curiosity and self-kindness. If at any point you feel overwhelmed, stop, take a break, and maybe do something grounding (like splash water on your face or look around the room and name objects) – that might mean a big protector or exile got stirred up, and you want to respect that and perhaps seek support.

Exercise 1: Meet Your Parts (Inner Check-In)

This is a basic mindfulness and writing exercise to start identifying some of your inner family members.

- Find a Quiet Moment: Sit down with a notebook or a notes app. Take a couple of deep breaths, relax your shoulders, and close your eyes if you’re comfortable.

- Focus Inside: Ask yourself gently, “What am I feeling right now?” or “Which part of me is most activated today?” Then just wait and see what comes up. It could be a feeling (tight stomach, heavy chest), a thought (“I’m worried about work”), or even an image (maybe you see a face or a younger version of you or some symbolic image like a knot or a fire).

- Note What You Find: Whatever comes, write it down as if you’re noting a character. For example: “There’s a part of me that’s anxious about that deadline, it feels like a tightness in my chest, kind of like a frantic squirrel.” Don’t worry if that sounds silly – the more creative your description, the better you might understand it! You might end up with a few entries, like a cast of characters: an anxious squirrel part, a critic voice that sounds like Mom, a tired slug part that just wants to sleep.

- Give Each Part a Bit of Attention: One by one, take what you wrote and imagine focusing on that part. In your mind, say hello to it. “Hi anxious part, I know you’re there.” You can even ask it, “What do you need right now?” or “Why are you feeling this way?” Write down any response you sense. Maybe the anxious squirrel says, “I’m scared we’ll fail that project.” Or the tired slug just gives you a feeling of heaviness (meaning it likely needs rest).

- Respond with Compassion: Thank each part for sharing. Write a short reassuring message from your Self to the part, like you’re the inner leader or a caring friend. “Dear anxious part, thank you for looking out for me. I hear that you’re scared. I will do my best to meet the deadline, but I’ll also make sure we take breaks so it’s not too stressful. You don’t have to do this alone.” Adjust the tone so it feels authentic to you.

This exercise helps externalize and identify parts, and it practices the habit of treating them (i.e., treating yourself) with kindness. Many people find that just writing it out like this creates some distance from overwhelming feelings and gives insight. It can become a daily or weekly check-in routine. Over time, you may notice the “regulars” – parts that frequently are active – and also become aware of more hidden ones as trust builds internally.

Exercise 2: Soothing an Upset Part (Step-by-Step Visualization)

Try this when you’re feeling emotional distress – be it anxiety, sadness, anger, etc. It’s like a mini self-therapy session to calm that specific part down.

- Pause and Breathe: When you notice you’re really upset (say you’re very anxious or very sad), pause for a minute. If possible, close your eyes and breathe slowly. Imagine with each breath that you’re creating a little safe space inside yourself.

- Find the Part in Your Body: Scan your body and see where the feeling is strongest. Is it a knot in your stomach? A lump in your throat? Tightness in your fists? Once you locate it, gently focus your attention there. You might even put your hand on that spot (like your chest or belly) and breathe warmth into it.

- Separate a Bit: Silently say to yourself, “I notice a part of me is feeling [anxious/sad/angry].” By wording it as “a part of me,” you remind yourself this isn’t all of you – there is a you observing it. This is you accessing your Self.

- Imagine the Part: See if an image comes to mind for this part. You might see yourself at a certain age, or a character (maybe that frantic squirrel again, or a scared child, or a furious ogre – anything). If you’re not visual, you might just sense what the part looks like or sounds like.

- Offer Comfort: Now, from your compassionate Self, interact with that image. If it’s a child version of you that’s scared, imagine giving them a hug or wrapping them in a warm blanket. If it’s an angry beast, maybe you give it space to vent safely, saying “I hear you’re really angry. I’m listening.” You could picture shining a calm light on it, or sitting beside it. The exact method isn’t important – what matters is the feeling of extending kindness and calm to that part.

- Ask What It Needs: While comforting, you can ask the part, “What do you need right now to feel a little better?” See what pops up. If it’s the child, maybe she says “I want to feel safe” – so you might imagine taking her to a safe place (like a fantasy garden or a room with cozy pillows). If it’s the angry part, maybe it says “I need justice!” – you could acknowledge that and say, “I know, you were wronged. It’s okay to feel that. I will help by [maybe writing in a journal, or asserting ourselves if appropriate].” You adapt in the moment to what the part communicates.

- Reassure and Return: Before ending the visualization, reassure the part that you (Self) are here and will continue to listen. For example, “I’m here for you. We’re in this together. You can rest now if you want, I’ll handle things for a while.” Then take a deep breath and gently open your eyes or bring your focus back to the room.

This exercise can take just a few minutes or longer if you have time. It’s essentially a quick version of IFS self-therapy: identify part -> unblend (separate) -> comfort -> listen -> reassure. It can turn a wave of emotion from something that crashes over you to something you ride and soothe.

Exercise 3: The “Parts Map” or Circle Exercise

This is more of a written or drawn exercise to get a bird’s-eye view of your inner family.

- Draw a large circle on a piece of paper. This circle represents your whole internal system.

- Now, think of the various parts of you that you’ve identified (through the above exercises or just generally in life). Start writing their names or roles in the circle. For instance, put “Inner Critic” in one area, “Worried Part” in another, “Little Joyful Kid” (yes, you have positive parts too, like playful or creative parts that maybe haven’t been around much lately but they exist!), “Angry Protector,” “People Pleaser,” “Sad Lonely part,” etc. Place them in the circle in a way that feels right – you might cluster ones that team up together, or put ones that conflict on opposite sides.

- Draw lines or arrows to show relationships or feelings. Maybe you draw a line between the Critic and the Sad part and label it “teases” or “criticizes,” showing that the critic tends to put down the sad part. Another arrow might be from the Sad part to the People Pleaser labeled “wants love from others.” You could draw the Angry part next to the Sad part with an arrow “protects” (since anger flares up when sadness is threatened). There’s no strict rule – it’s your map of your parts.

- In the center of the big circle, write “Self” and maybe draw a heart or a calm smiley face – something to represent your core Self.

- Now reflect on the map. Which parts are closest to Self (easier for you to access) and which are farthest (maybe exiles you don’t often feel directly because protectors block them)? Which parts are most dominant lately? Are there parts you wish you had more access to (like “I miss my playful part, it’s been exiled by work stress”)? This map is a living diagram; you can redraw it over time as things change.

The parts map is a great visual way to externalize your inner world. Some people like to keep it and update it occasionally. It can also be something you bring to therapy if you choose to see a professional – it gives them a snapshot of your inner cast. TherapyWorkbooks and resources often have worksheets for parts mapping as well. (For instance, the Internal Family Systems Workbook (200+ Pages) from TherapyWithCT includes guided activities like parts mapping, journaling prompts, and more to help you deepen this self-exploration in a structured way.)

Exercise 4: Daily Self Check-In

Finally, a simple habit: each day, take 1-2 minutes to do a quick IFS-style check-in. Ask yourself, “Who’s running the show right now inside me?” If you’re about to start your workday and you feel frantic, maybe your Inner Taskmaster Manager is front-and-center – say hi to it, acknowledge its drive but maybe invite it to ease a bit so you’re not too stressed. If you’re relaxing in the evening and suddenly remember an email you forgot, notice if an anxious part jumps in – tell it “I hear you, I’ll handle it tomorrow, let’s rest now.” Going to bed, you might notice a lonely part – give it some comfort rather than scrolling your phone to push it away. These tiny moments of awareness and care add up and prevent parts from completely hijacking you.

Finding Support and Next Steps

Exploring your inner world can be fascinating and liberating, but it can also stir up emotions. You don’t have to do it all alone. If you find IFS intriguing and helpful, consider finding a therapist trained in IFS to guide you, especially if you have significant trauma or very intense feelings that are hard to navigate solo. An IFS therapist will skillfully help you stay in your Self while working with challenging parts, providing a safe space for deeper healing.

There are also many resources to support your journey:

- IFS Books & Articles: If you like to read, the book “Self-Therapy” by Jay Earley is a popular step-by-step guide to using IFS on your own. There’s also “No Bad Parts” by Dr. Richard Schwartz, the founder of IFS, which beautifully explains the IFS perspective and is very affirming – as the title suggests, it reinforces the idea that every part of you is valuable.

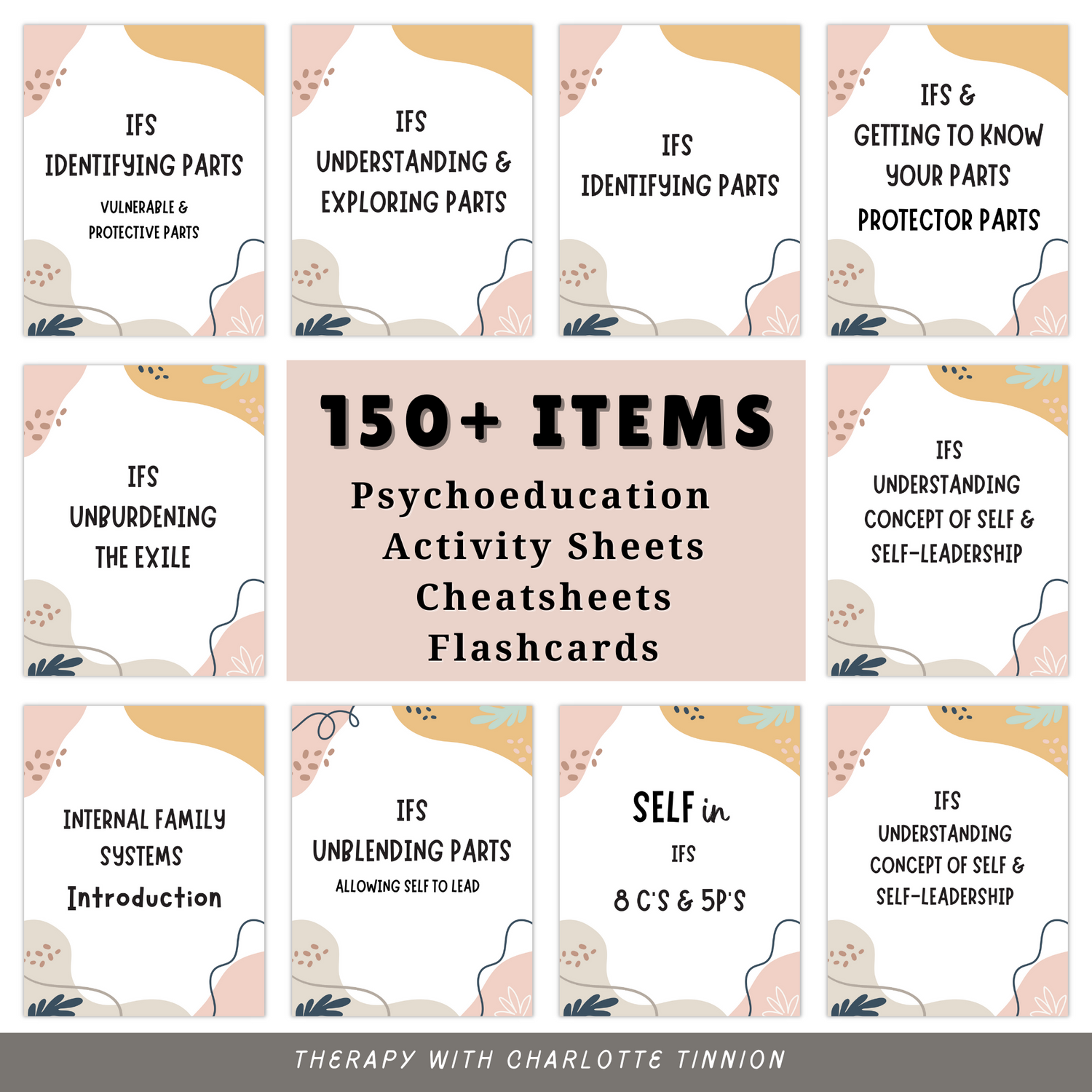

- Workbooks and Tools: Hands-on materials can be great. Check out the IFS (Internal Family Systems) Collection at TherapyWithCT for user-friendly resources. They offer things like the IFS Workbook we mentioned, IFS flashcards, and journals with prompts. These can give you exercises to do, questions to ponder, and even affirmations to use. For example, IFS flashcards might have coping statements or insights for common parts (e.g., a card for the Inner Critic with a reminder of how to respond to it). Such tools can keep you engaged and make the learning interactive.

- Support Groups or Workshops: Sometimes there are IFS practice groups (online or offline) where people share experiences and do guided exercises. It can be reassuring to connect with others who are learning this model – you realize wow, we all have parts! It normalizes it even further and you can swap tips on what’s working.

- Therapy (Individual or Group): Of course, therapy is a direct way to experience IFS. In IFS therapy sessions, you might do a lot of closed-eye work (to focus inside) with the therapist’s voice helping you stay with whatever comes up. It’s a gentle, client-led process. Group therapy in an IFS style might involve each person working with their system while others support – but that’s more specialized. Starting with individual therapy is usually best if you want more support.

One more point: IFS and Other Therapies. IFS can work alongside other approaches. For example, if you’re also practicing mindfulness meditation, you’ll find IFS fits nicely (parts work is a kind of mindful self-awareness). Or if you’re on medication for anxiety/depression, you can still do IFS – the medication might even give you enough calm to better access Self. IFS doesn’t conflict with things like cognitive-behavioral techniques either; you can use CBT techniques on specific parts (e.g., help a part challenge its distorted thinking) within an IFS framework. The key is that IFS adds the element of relationship to self, which enriches whatever else you’re doing for self-care.

Conclusion: Embrace Your Internal Family

Embarking on Internal Family Systems work is like embarking on a journey to meet yourself – all the different parts of yourself – and to cultivate an inner atmosphere of understanding and harmony. It’s truly a gift of self-love. Instead of living at the mercy of anxiety or self-doubt, you learn to hold the reins gently as your Self, guiding your inner family with patience. There will still be bumps on the road (we’re all human, and life will trigger our parts now and then), but with IFS tools, you’ll recover your balance more quickly and even use each challenge as a chance to get to know yourself better.

You are not broken – you’re beautifully complex, and every part of you exists for a reason. By listening to those reasons and fulfilling those needs in healthier ways, you will experience change. Anxiety can transform into proactive energy, depression into depth and empathy, trauma into resilience, and low self-esteem into a solid sense of self-worth. It doesn’t happen overnight, but it happens as surely as day follows night when you consistently bring compassion to your inner world.

Finally, remember that help is available. Whether it’s through resources like the TherapyWithCT website (which strives to make therapy concepts accessible and practical) or professional counseling, you don’t have to figure it all out by yourself. This guide is a starting point – a friendly nudge to get curious about your inner life. The next steps are up to you, and they can be as small and gentle as you need.

Be patient and playful if you can – yes, playful! Approaching this with a bit of lightness can ease the fear some parts may have. You might even internally joke with your parts (“Alright Committee of Inner Critics, I hear ya, but take five while the CEO Self steps in”). Find what tone works for you.

We hope this comprehensive guide has demystified Internal Family Systems for you and shown you how it can directly apply to the very real issues of anxiety, depression, trauma, and self-esteem. You’ve got the knowledge and some tools – now the compassionate exploration begins. Wishing you a healing journey as you befriend your internal family!

Key Takeaways (for quick recap):

- IFS (Internal Family Systems) is a therapy that sees your mind as composed of different parts, with a core Self that is wise and compassionate. You’re not “crazy” for having inner conflicts – it’s normal, and those parts have reasons for what they do.

-

Common Parts: Managers try to keep you safe and in control (often through worry, criticism, perfectionism), Firefighters jump in to numb or distract from intense pain (through things like overeating, substance use, anger outbursts), and Exiles carry deep wounds and emotions from past hurt (like trauma or rejection)

. All parts, even if extreme, are trying to help or protect you in the only way they know how. - Self: Your core Self is the healing agent – the goal of IFS is to help you lead your life with Self qualities like calm, courage, and compassion. When Self is in charge, your parts trust you more and don’t have to act out as extremely.

- Anxiety: In IFS, anxiety comes from parts that are scared and trying to prepare for or prevent danger. By listening to your anxious parts (like the inner Worrier or Critic) and reassuring them, you can calm the chaos. Next time you’re anxious, try saying “I hear you” to that worried voice, rather than “go away.” It helps!

- Depression: Depression often involves parts that have lost hope or are shutting down to protect you from pain. IFS works by gently engaging with those parts – appreciating the protection, then healing the hurt (exiled) parts carrying despair or shame. This can gradually bring back a sense of purpose and self-worth.

- Trauma: IFS is a powerful approach for trauma because it doesn’t force you to relive anything until your inner system is ready. By getting the okay from protective parts, then healing the wounded exiles, you can release the trauma’s grip on your life in a safe, controlled way. No part of you is beyond healing. Many have used IFS to overcome even severe PTSD, with patience and support.

- Self-Esteem: That harsh inner critic can be transformed. IFS helps you replace self-judgment with self-compassion. As your inner parts feel more loved and understood, your overall feeling about yourself improves. You learn to value all parts of you, which translates into healthy self-esteem on the outside.

- Practical Tools: Start by noticing your parts (journal your feelings as voices or characters). Practice self-talk that’s compassionate – speak to yourself as you would to a dear friend. Try the visualization exercises to comfort upset parts. Mapping your parts can bring clarity. These techniques get easier with practice.

- Support: You’re not alone. There are IFS resources (like workbooks, therapy tools, and communities) and therapists who specialize in IFS. Reaching out for help is a sign of strength and self-care.

- Be Patient and Curious: Healing is a journey. Some days you’ll feel really in tune with your Self, other days parts will take over – and that’s okay. Every time you notice what part of you is active and respond with curiosity instead of judgment, you’re making progress. Over time those small shifts lead to big changes in how you feel and behave.

- No Bad Parts: This core IFS motto means exactly that – none of your parts is bad or wrong. They all deserve a voice and compassion. When you truly believe that, you’ll experience a profound shift in how you relate to yourself and others. You become whole, not by eliminating parts of you, but by embracing them.

We hope you feel supported and encouraged to explore IFS as a tool for improving your mental well-being. May you discover the inner harmony that comes from befriending your internal family!